Terminé le 22.01.23

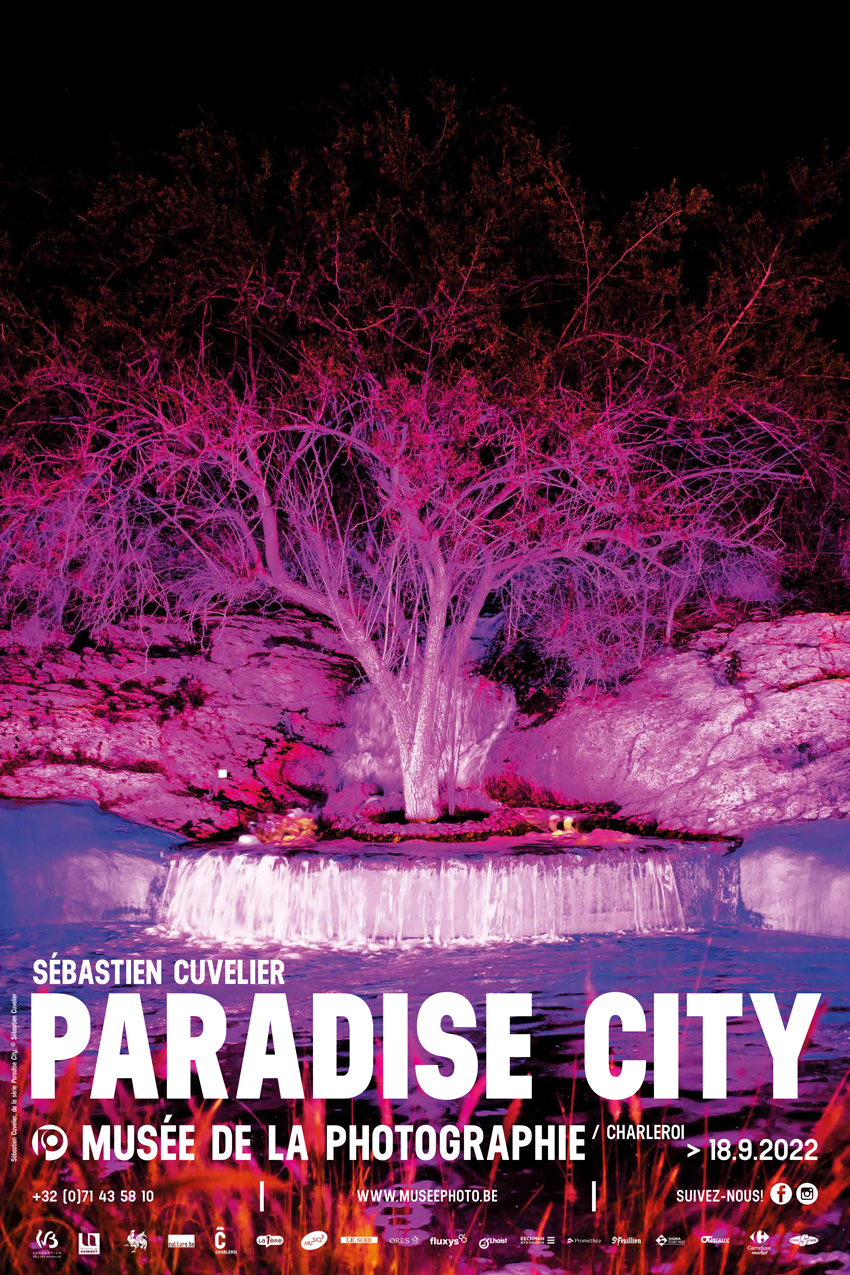

Sébastien Cuvelier. Paradise City

In Paradise City, Sébastien Cuvelier focuses on the concept of Iran as a mythical country. In the 1970s, Sébastien Cuvelier’s uncle set out to explore those lands, keeping a diary of his journey. Inspired by this manuscript, the artist

went back there on several occasions to build his own picture of the country. Through this project combining archives and personal vision, he creates a dialogue between Iran before the fall of the Shah and the country as it is today, in search of an elusive and dreamlike version of paradise.

“The only true paradise is the paradise we have lost“

1971 was the 2,500th anniversary of the great Persian Empire. To celebrate, the Iranian Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, hosted extravagant festivities with the ruins of Persepolis at their heart. My uncle was a 22-year-old civil engineering student at that time, with a pronounced taste for culture and travel. In anticipation of the celebrations in Iran, he and two friends bought a Volkswagen Kombi and drove the 6,000 kilometres from their home in Namur, Belgium.

My mum was very proud of her little brother. Upon his death, she handed me her copy of his travel journal. He had written it during his adventures, collecting a briefcase full of negatives at the same time. Mum had later typed the journal up for him, distributing it to family and friends. She had written her maiden name on the first page of the manuscript, the way schoolchildren do.

In 1979, eight years after my uncle’s trip, a revolution overthrew the Shah and quickly turned Iran into a country fantasised as an Islamic paradise. Everything was irreversibly changed. The Iranian youth born after the revolution – almost half the population – have experienced little of the world beyond their padlocked country. They live under the stifling hand of a religious and authoritarian power that tries – mostly in vain – to control access to social media and foreign television channels.

The last chapter of my uncle’s journal, ‘Iran, Paradise Lost’, could be used to describe the state of modern-day Iran: a former great civilisation, mired in regional and global conflicts, and paralysed by economic sanctions. The country’s young, connected population yearn to leave – they seek paradise, but are un- sure where to look.

And yet, the sheer concept of paradise is inherently Iranian. The word paradise comes from old Persian paridaida – meaning walled garden. When the Greeks first invaded Persia in the fifth century BC, they were so impressed by the Persian royal gardens that they adapted the word as paradeisos – a slice of heaven in the form of a garden. Many years later, Abrahamic faiths associated paradise with gardens, such as the Garden of Eden in Christianity. By extension, Persian carpets and their leafy motifs represent paradise too.

It is therefore only natural that this word resonates in all corners of a country where history is full of nostalgia, people are deeply romantic and flowers are everywhere. ‘Paradise’ in Iran has become synonymous with shopping malls, holiday destinations and even entire cities – like Pardis Town, a surreal city resembling concrete clusters growing in a Mars-like landscape under construction outside of Tehran.

In reaction, contemporary Iranian youth have developed their own notions of paradise. For some, it is a small village in northern Iran, where they can escape Tehran’s notorious smog. For others, it is a secluded beach on a small island in the Persian Gulf, away from religious and political constraints. For others still, it is somewhere in Europe or North America – far from Iran – where they can begin a new life.

But for most people I met, their paradise is anchored in Persia. Its existence is linked to hope, the quest for change, the desire for a new beginning. These feelings bring with them an ever-present hint of nostalgia, seen in family tales, photo albums or through the fading memory of distant cousins who emigrated to find their own paradise city.